Tags

adventure games, games, gaming, Gamma World, Infocom, post-apocalypse, review, rpg, Steve Meretzky, Superhero League of Hoboken, superheroes, video-games, zaniness

Adventure games, especially where intended to be comedic, tend towards the zany. These kinds of games are full of eccentric characters, bizarre inventory items, and anachronistic situations. The underlying tone is zaniness: a preference for fun, creative un-seriousness over developed themes or coherent settings. Legions of pathetic heroes — dabblers and dilettantes, ensigns and apprentices — fill the ranks of adventure game protagonists. Adventure game puzzles typically rely on encountering and overcoming ad hoc situations, the sort not the domain of a serious professional, but rather a series of unusual predicaments that can be solved at a leisurely pace by an underemployed kleptomaniacal packrat.

Steve Meretzky’s adventure games (apart from a few standouts like A Mind Forever Voyaging) are prime examples of this zany tendency. This can be seen in his first game, Planetfall where you play a glorified janitor (the same idea was later taken up in Sierra’s Space Quest games), through the adaptation of Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, to the more sleazy later titles of Leather Goddesses of Phobos, and the Spellcasting 101 series. The culmination of this approach was his last game for Legend Entertainment, and his penultimate adventure game overall,1 Superhero League of Hoboken.

For those unfamiliar: Superhero League of Hoboken (hereafter SLoH) is a hybrid RPG/adventure game. It has a grid based world-map, a party of combatants with stats and equipment that fight battles, but the game’s plot, structure, puzzles, and humour are all from the adventure game. The core premise is that in a post-apocalyptic Tri-State area, a league of costumed superpowered heroes in the ruins of Hoboken have to traipse about the wasteland, fighting mutants, enduring radiation, and solving whacky adventure game problems all ultimately caused by a sentient jack-in-the-box, Doctor Entropy.

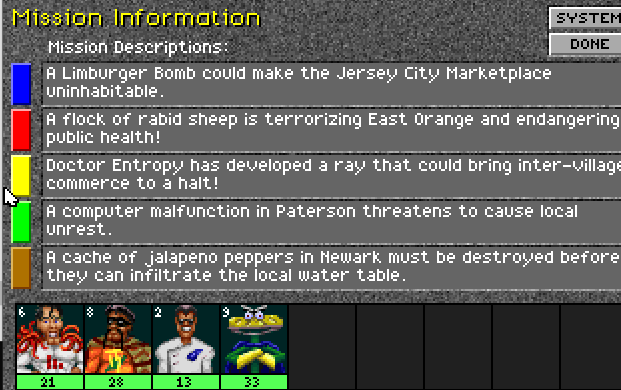

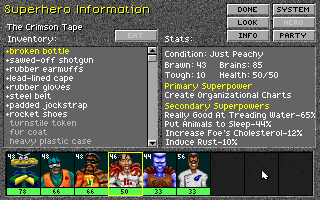

The quests are all either resolved through finding the right object (sometimes in a short puzzle chain) and bringing it to some place, or by utilising one of the heroes unique abilities. As far as heroes and gear go, SLoH presents like the opposite roleplaying game hero fantasy to X-COM: UFO Defense which also came out in ’94. Instead of power suits and plasma pistols, they have jockstraps and broken bottles. It’s Rincewind-with-half-a-brick-in-a-sock humour.

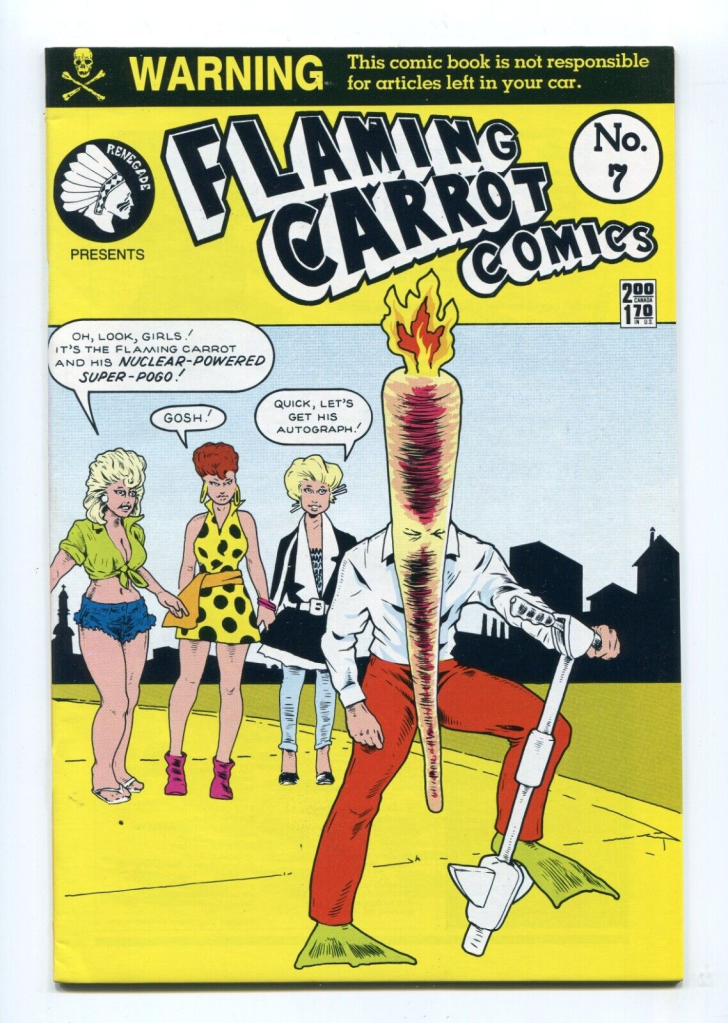

The superhero with a weak or bizarre power is its own rich subgenre, usually but exclusively used for comedy. The Flaming Carrot comics of the 80s developed into the Mystery Men film in the 90s. In TV, Misfits in the 00s paved the way for Extraordinary, which is airing now. SLoH encompasses both ways the ‘weak hero’ approach can go. The heroes can be comedy one-notes where the power is actually weak (the Iron Tummy can “eat spicy food without distress”, which is used exactly once as indicated by the quest in the screenshot above). Or, they can be unexpected powerhouses where the power is actually quite good when you think about it, like dramatically increasing cholesterol or inducing rust.2 The game can exploit the humour in both directions this way: either the powerful hero is a joke, or an apparent joke is a powerful hero.

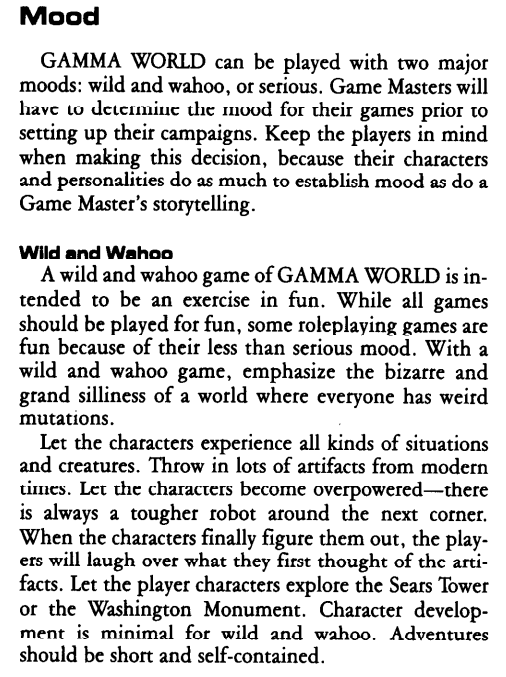

As for the post-apocalyptic side of things: absurd situations abound in game series like Fallout, Wasteland, and the earlier novels and tabletop RPGs that inspired them such Gamma World. Woops! the reportedly terrible post-nuclear-holocaust sitcom aired in ’92: maybe in that immediate post-Soviet collapse era, it was even easier to be silly about nuclear apocalypse, or more likely, perhaps by that point it had permeated in popular culture (like superheroes) for so long that its tropes were easy pickings for comedic treatment. During the end times, anything and everything can appear, and the bizarre is easy to justify. In this way, the post-apocalypse shares much in common with the superhero genre with its proliferation of mutations and science experiments gone wrong.

Silly names and deflating self importance are recurring elements in zany humour, and SLoH combines both. ‘Hoboken’ is an inherently funny sounding word. It’s a lot ‘Scranton’ used in Trixie the Giraffe Necked Girl from Scranton in Sam & Max Hit The Road. The humour here is bathetic, the bombacity of a Superhero League and the exoticism of a Giraffe Necked Girl is punctured by the paltry provincialism of Hoboken and Scranton respectively. This is the same approach taken in the comedic Great Lakes Avengers comics, which also feature Z-list heroes out in the sticks of Milwaukee.

There is perhaps a cultural and class element here too. Hoboken is on the outskirts of a great city. Compared to New York across the river, it was perhaps seen as more ugly, post-industrial, relatively deprived and charmless. This mirrors the relationship Slough (another funny word) has to London. Indeed, the original British iteration of The Office television series was set in Slough for precisely these associations. The heroes in SLoH are also coded as more working-class, or at most, middle-manager types like the Crimson Tape. They carry plungers and wear safety vests and rubber gloves. Like all classic adventure game protagonist losers (lovable or not), they can’t be too successful, professional or organised.

A weakness that permeates zany adventure games, and is very much present in SLoH is that humour that relies on deflating is hard to sustain across a work, and silly names and puns becoming tiring very quickly. SLoH is at its weakest where it relies on rapidly dated cultural references (especially seen in the random enemies), and is at its strongest when its presenting short, picaresque scenes at the culmination of various quests that paint a world that is silly but has a distinct life of its own. Anachronism, 4th wall breaks, and punctured expectations can all work in moderation but if constant they can undermine the thinly suspended reality of the story, and the test the audience’s investment in the dramatic stakes necessary to sustain interest in a longer-form game or story. If any silly thing can and does happen, then a narrative is lost and all that remains is the individual entertainment of each absurd situation.

As interactive fiction has gradually left its text adventure roots behind, zaniness of heroes, puzzles and setting is longer so ubiquitous. While comedy games have continued to do very well in the annual Interactive Fiction Competition, the most successful of them like Hunger Daemon (2014), Brain Guzzlers From Beyond (2015), The Wizard Sniffer (2017), where still somewhat zany, tend to balance this with enough dramatic stakes and puzzles embedded in an internally consistent setting. As shorter games, they remain engaging and amusing for their play length.

Zaniness continues to haunt graphical adventure games, and a lot of this is due to a blanket of nostalgia that smothers creative impulses in a suffocating layer of nodding references. It’s hard to make something good if you’re self-consciously trying to recreate a past form that was only sometimes good itself. A joke can be funny in its time, but many adventure games try to recreate joke formats that were played out over thirty years ago. Nostalgic adventure games like Thimbleweed Park can have a lot of promising elements— fun situations, characterisations, puzzles and dialogue— but weigh themselves down by constantly inviting poor comparison with their predecessors. Where adventure zaniness still works is in the short concentrated form, such as with the very silly Investi-Gator which packs in a handful of absurd and amusing mystery cases with a lot of jokes for a very short episodic play time.

Where zany works succeed, they’re either like Monkey Island which balances the very silly comedy with distinct characters, setting, and an actual plot; or they’re like Flaming Carrot where the bizarre situations are distinctly drawn and engaging on their own merits and the works are short enough to sustain interest in this. Steve Meretzky managed to explore adventure game zaniness in a dozen or so commercial games. It was the mood he was most comfortable with and at his best, the games could be creatively fecund, surprising, and fun. But his best comic work has a solid foundation of story and game design. SLoH‘s joke monsters grow tiring very quickly, the basic RPG gameplay lacks tactical depth and cannot sustain a game by itself, and so what is left is a string of amusing incidents tied together by some very transparent adventure game puzzle chains. Silly names, anachronisms, and bathos are best enjoyed as a spice to a more nutritious meal rather fare on their own.

- The last of Meretzky’s adventure games was, to my knowledge, The Space Bar, set in ‘The Thirsty Tentacle’ on the planet Armpit VI. ↩︎

- The non-zany web serial Worm managed to draw out 1.6 million words of story taking seriously the premise of the weak sounding but actually strong power (in this case ‘power to control bugs’). ↩︎